By Lori Culbert

Published Aug 06, 2024

Last updated Aug 06, 2024

Lynda Fletcher-Gordon inside the Purpose Society Site in New Westminster on July 29

After being greeted by the happy aliens on the Starship Safe Injection Site’s colourful sign, you walk by a large kitchen where food hampers are made and past an oval table where the vulnerable clients are encouraged to gather.

Then a martian poster directs you around a low partition wall, where eight small desks sit in orderly rows, bright green or blue chairs tucked underneath. It’s reminiscent of an elementary school classroom, except for the bags with clean drug-use supplies dangling from each desk.

There are no stainless steel booths in New Westminster’s overdose prevention site, setting it apart from many others in Metro Vancouver, says Lynda Fletcher-Gordon, the veteran leader of the non-profit group that runs it.

The homey design is meant to encourage clients to stay for a coffee and chat with staff, who hand out harm reduction kits, food and referrals to treatment or other services.

Article content

Article content

In the midst of a toxic drug crisis, which has killed nearly 15,000 British Columbians since 2016, the Lower Mainland Purpose Society for Youth and Families added this site to the trove of health services it has offered for four decades.

Article content

Article content

“People were dying around us,” explained Fletcher-Gordon, the society’s co-founder and program director.

Article content

Article content

The Starship is one of 51 supervised consumption sites across B.C., a number that has been “rapidly expanded” to reduce drug poisoning deaths, the Mental Health and Addictions Ministry said in a statement. Between January 2017 and April of this year, nearly 29,000 overdoses were successfully reversed at these locations.

Advocates argue this is one important medical tool to keep people alive during the public health emergency.

“Not only are we able to prevent death and harm, we’re also increasing connections to health-care resources and access to substance-use services that could include things like treatment,” said Jennifer Conway-Brown, a harm-reduction lead with Fraser Health, which oversees the Starship site.

Article content

Article content

“They really do save lives.”

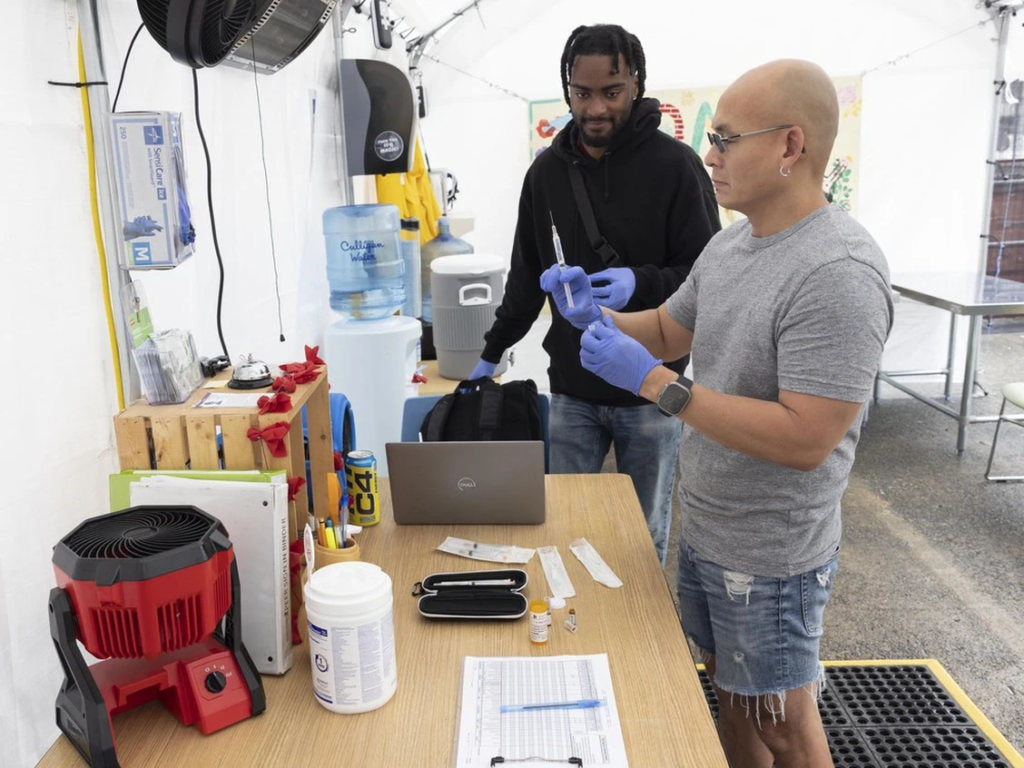

RainCity peer witness supervisor Jason Ong, right, and peer support specialist Delano Flintroy-Scott pre-load naloxone kits at the Thomus Donaghy overdose prevention site in Yaletown. Photo by Jason Payne /PNG

Some people, though, are opposed to scenes outside these sites, where marginalized clients can congregate, creating a sense of disorder in the neighbourhood.

Article content

Article content

Other critics are against what happens inside, including federal Conservative Leader Pierre Poilievre, who vowed to withdraw federal funding and potentially close the sites if he’s elected prime minister. He dismissed them as nothing more than “drug dens.”

Article content

Article content

That was the same vernacular used by B.C. Tory Leader John Rustad in February, when he backed Richmond residents who were against a proposed overdose prevention site.

New Westminster: 52 lives saved

Article content

Article content

In New Westminster, neighbouring businesses interviewed by Postmedia News had mixed reactions to the Starship.

Article content

Article content

Russell Masangkay, co-owner of Mindset Barber Shop across the road from the site, said the drug users don’t bother his business and he hasn’t detected an increase in crime.

Article content

Article content

A woman who has worked for 20 years in a sushi restaurant beside the site, though, said she has called police and city bylaw officials multiple times with concerns about garbage on the street and people passed out on her property. The woman, who declined to give her name, said she didn’t feel safe and questioned whether there is a better way to help the site’s clients.

Article content

Article content

New West police were unable to tell Postmedia if calls for service have increased near the site.

Article content

Article content

Fletcher-Gordon said her agency does what it can to address any concerns, including speaking with worried neighbours, cleaning up messes left by clients, and reminding people not to sleep or use drugs in front of the Purpose Society building in downtown New West.

“We do what we need to do to minimize the impact on the community,” she said.

Article content

Article content

This is vitally important, she added, because keeping the site open is critical: It had 1,819 visits from April 2023 to March 2024, and during that time reversed 52 overdoses.

Article content

Article content

Harm-reduction officials say Metro needs far more of these sites to keep people alive. Fraser Health doesn’t operate any in Burnaby, Delta or the Tri-Cities, for example, but wants to eventually have a site in every city in its region, Conway-Brown said.

Article content

Article content

In order to find more locations, though, it would be better if neighbours were supportive. So, how to balance those two competing interests in this life-and-death quandary?

Article content

Article content

“That’s the big question,” said Dr. Mark Lysyshyn, Vancouver Coastal Health deputy medical health officer.

Article content

Article content

His health authority oversees 14 sites, which he argued are crucial to protect people from poisoned street drugs until society properly addresses the root causes of addictions.

“We’re just trying to stop people from dying,” he said. “Unfortunately, having these services sometimes makes people less supportive of even entering into the discussion about the solution.”

Article content

Article content

Most complaints the health authority receives, though, are about people acting strangely on the street, such as yelling or loitering, and not about serious crimes, Lysyshyn added.

Article content

Article content

Yaletown: New, less visible site

Article content

Article content

A Yaletown resident sued Vancouver Coastal Health and others over the former location of an overdose prevention site, arguing it turned the area into “a centre point for crime and public disorder.”

Article content

Article content

After city hall didn’t renew its lease, the Thomus Donaghy OPS moved a few blocks away in April, to a parking lot behind a supportive housing building. The new site generates some complaints from businesses and condo residents, but fewer than the original location because it’s less visible from the street, Lysyshyn said.

Article content

Article content

Some neighbours, such as the owners of a vintage store that has now closed and a high-end dress shop, have expressed concerns about crime and vandalism since the site arrived in April. Vancouver police didn’t provide statistics for this story, but in June told Postmedia reporter Joseph Ruttle that calls for service increased on the Howe Street block after the site opened and that neighbours’ frustrations about street disorder were “legitimate.”

Raincity Housing, the non-profit that runs the Thomus Donaghy site, wants to be responsive to neighbours’ concerns and has met with many of them to explain the work it does to keep people alive and connect them with services, said associate director Amelia Ridgway.

Article content

Article content

“I think people are really struggling to understand what’s happening with this poisoning epidemic,” she added.

The new site primarily serves people who live in the downtown core, and has had 5,362 visits since April. Ten overdoses have been reversed by the staff, all people with drug-use experience whom Ridgway describes as doing heroic work during a devastating crisis.

Article content

Article content

“This site is set up for anybody from any walk of life, for any reason why they’re using drugs, to come and feel safe and supported, and to reduce the risks,” said Jodie Millward, a RainCity senior vice-president.

Article content

Article content

The new location is entirely outdoors, which allows it to have one tent with four booths for injecting as well as a separate tent with six tables for people who smoke drugs. The inhalation tent has a heater for cool days and two large crates to temporarily house clients’ dogs.

The majority of the 14 sites overseen by Vancouver Coastal Health — a mix of permanent, mobile and in-hospital locations — are near the Downtown Eastside, home to Insite, Canada’s first safe injection site, as well as the busy Overdose Prevention Society. But there are also sites in Squamish, Sechelt and Powell River, as there is demand for these services in other areas, Lysyshyn said.

Article content

Article content

Surrey: Not enough services

Article content

Article content

Fraser Health runs a dozen supervised consumption sites across its region, in places such as Abbotsford, Chilliwack and Langley, Conway-Brown said.

Article content

Article content

Article content

Article content

Surrey has just one dedicated location for injecting and smoking drugs, Safepoint in Whalley, which also offers drug-testing, naloxone training to reverse overdoses, and connections to health and social services. Just down the road, a sobering centre offers some limited services for injection users.

Article content

Article content

That’s not nearly enough resources to support Surrey’s growing population and large geographic size, argued Anmol Swaich, a community organizer with the Surrey Union of Drug Users.

In early July, Swaich’s organization ran a pop-up inhalation tent for two nights to “draw attention to how neglected Surrey is” when it comes to supervised consumption sites, she said.

Article content

Article content

Ideally, Surrey, which experts predict could surpass Vancouver as Metro’s largest city, needs something similar to Vancouver’s 20-year-old Insite, which offers supervised injection on the ground floor, detox upstairs and other health services, she said.

Article content

Article content

This issue should be important to all British Columbians, she insisted, noting members of the Surrey drug users’ group come from all walks of life. That is backed up by coroner’s data that shows overdose victims span from people struggling with homelessness and mental illness to those who are employed with homes and families.

Article content

Article content

“We have a significant representation of South Asian people, Indigenous Peoples, young adults to seniors, newcomers and those who immigrated several decades ago, people whose families have lived in Surrey for generations,” said Swaich, a Simon Fraser University grad student in health sciences.

Some members turned to drugs to cope with poverty, the unaffordable housing market, chronic pain and other physical health issues, and being unable to access the social supports they need, she said.

Contrary to the complaints about supervised consumption sites, said Conway-Brown, research shows neighbourhoods with these services have fewer needles and pipes discarded on the streets, fewer people using drugs and overdosing in public, and a reduction in the need to call police, fire and ambulances.

Article content

Article content

Eight of Fraser Health’s 12 supervised injection sites also have inhalation tents, and Conway-Brown said the region would like to expand witnessed smoking areas to every community in the region.

Article content

Article content

Smoking deadlier than injecting

Article content

Article content

A coroner’s report released this week documented a recent shift in lethal poisonings: two-thirds of people who died in 2024 were smoking drugs, while only one in 10 were injecting.

Article content

Article content

Provincially, half of B.C.’s supervised consumption sites offer smoking areas, but there are none in the Interior or the north, where the coroner documents the most lethal poisonings per capita.

The Starship doesn’t have sufficient venting to allow smoking, so staff can only witness people injecting drugs inside. But it has created a short-term solution: clients inhale their drugs outside the centre’s backdoor, where employees use a security camera to monitor the 28 people, on average, who drop by to smoke every evening.

Article content

Article content

In June, Purpose Society staff reversed six overdoses — all of them among the smokers outside, and none among those injecting inside. And the front desk handed out nearly 500 smoking kits, but only half as many injecting kits.

Article content

Article content

Fletcher-Gordon has spoken with the city and Fraser Health about short- or long-term solutions to more formally include inhalation services at the Starship. It’s expensive, she acknowledged, but also urgently needed.

Article content

Article content

“We either do it or people will continue to die,” she said.

While recognizing that not everyone loves the idea of supervised consumption sites, she maintained they must be allowed to continue, both to keep people alive and to support them when they’re most in need.

In June alone, the Purpose Society’s health centre distributed 2,000 meals or snacks, 230 overdose-reversing kits, and made 23 referrals for housing, recovery and other services.

Article content

Article content

“We need (these sites) because we need to maintain our humanity. And we need to absolutely keep our eyes focused on what’s good and what’s the right thing to do,” she said.

Article content

Article content

“(And it) is much more economical to provide planned and organized services than to leave things to a continual crisis response.”

Article content

Article content